January 1, A.D. 404, marked Rome’s last known gladiatorial games.

What part did an obscure Christian monk from the East play in this epic change in Roman entertainment?

This is the story of St. Telemachus, whose festival is celebrated today and has been remembered throughout the last 1600 years.

You may have never heard of the name. Or you may know it as the name of the son of Homer’s Odysseus (Ulysses), who was tutored and protected by Mentor while his father was away fighting in the Trojan War.

Here’s the background of the little-known monk, how he brought an end to the Imperial gladiatorial games, and how the story has been adapted over the centuries until it was used 40 years ago by an American President at an international event.

Origin of Telemachus Narrative

The church historian Theodoret, bishop of Cyrrhus in Syria, first told the story in the 5th century in his succinctly titled Ecclesiastical History, a History of the Church in 5 Books from A.D. 322 to the Death of Theodore of Mopsuestia A.D. 427. Theodoret relates how a monk from the eastern part of the Empire named Telemachus came to Rome and saw the gladiatorial games when:

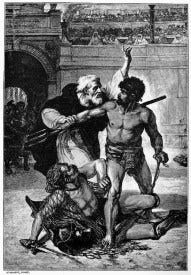

“After gazing upon the combat from the amphitheatre, he descended into the arena, and tried to separate the gladiators. The sanguinary spectators, possessed by the demon who delights in the effusion of blood, were irritated at the interruption of their cruel sports, and stoned him who had occasioned the cessation.”

Location of the Martyrdom of Telemachus

The amphitheatre mentioned here suggests the Colosseum, or the Flavian Amphitheatre. The “arena” (Latin: sand) refers to the sand covering the wooden floor to absorb the blood of the games. Theodoret continues

“After being apprised of this circumstance, the admirable emperor numbered him with the victorious martyrs, and abolished these iniquitous spectacles.”

This was the Christian Emperor Honorius, the son of Emperor Theodosius I.

Abolishment of the Gladiatorial Games

The gladiatorial games had been declared “ended” several times previously, though unsuccessfully. Numerous Christian emperors, including Constantine (who first made Christianity a “legal” religion in Rome), Constantius, and Julian, had “abolished” the games.

Even Emperor Theodosius I, who made Christianity the official religion of Rome in the 4th century, published an edict against the games. But it was not until Honorius, who recognized Telemachus’ martyrdom, that the games ended. This time, it stuck because six years later, the Visigoths, under Alaric, sacked Rome, a significant event in the decline of the Roman Empire. For a story on how Theodosius ended the Olympic Games, see here.

Though Theodoret wrote this story more than a millennium and a half ago, it has been famously recounted several times — for different purposes — including during our generation.

8th and 9th Centuries story of Telemachus

A popular form of medieval literature was martyrology. The Martyrology of Ado Archbishop of Vienne in Lotharingia in the mid-9th century relates how St. Almachus (another name for Telemachus) opposed the games and was slain by the gladiators on the orders of Alpius, prefect of Rome, during the reign of emperor Theodosius, father of Honorius.

The place and date match in this story, but not the year. Was this the same martyr? Ado’s work and chronology are based on that of the Venerable Bede — from what is now England — from a century earlier.

16th Century story of Telemachus

Over a thousand years after the martyrdom of Telemachus, John Foxe included him in his well-known Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. The context of this book is significant. Foxe was a contemporary of Queen Mary Tudor, aka “Bloody Mary.” She earned this name for killing about 300 Protestants as she assumed the English crown after her very Protestant half-brother, King Edward VI. (See explanation here.)

His book recounts the martyrdom of many in the West, emphasizing the 14th through the 16th centuries, ending with Mary.

In his book in 1563, he expands the story to say that Telemachus came to Rome’s churches to spend Christmas and was stirred by the thousands who flocked to see the gladiatorial games. Despite his failure to convince them of their cruelty and wickedness, his death

“turned the hearts of the people”

and opened their eyes to the brutality of their conduct and “the hideous aspects of their favorite vice.” As he fell dead in the Colosseum, no further gladiatorial games were held there.

19th Century Story of Telemachus

Alfred Lord Tennyson, poet and laureate of Great Britain during Queen Victoria’s reign, tells the story of Saint Telemachus. The monk felt called by God to leave his seclusion and seek out “the fire to the West,” the Christian city of Rome.

Borne along by a crowd of men, he was drawn into the Colosseum. Amongst the slaves, the dead animals, the dust, and the blood, he saw gladiators viewed by eighty thousand spectators. He moved down the stairs and into the arena, placing himself between the combatants.

‘Forbear, In the great name of Him who died for men, Christ Jesus!’

As silence fell, it was replaced by the snake-like hiss of the audience, replaced by the “deep roar as of a breaking sea” like a shower of stones from the spectators stoned him dead, followed by silence. “His dream became a deed that woke the world.” Throughout the amphitheatre ran a “shudder of shame” that came to the attention of Honorius, who decreed

That Rome no more should wallow in this old lust

Of Paganism, and make her festal hour

Dark with the blood of man who murder’d man.

20th Century Story of Telemachus

In 1984, American President Ronald Reagan told the story of “the little monk” at the annual National Prayer Breakfast in Washington, D.C. His story is the narrative of a Hollywood epic, as it could only be orated by the Hollywood actor he once was. At this international event, which began in 1953, President Reagan recounted the story in this way:

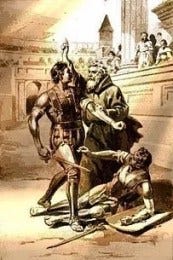

This power of prayer can be illustrated by the story that goes back to the fourth [sic] century — the monk… followed a crowd into the Coliseum, and… he saw the gladiators come forth, stand before the Emperor, and say, ‘We who are about to die salute you.’ And he realized they were going to fight to the death for the entertainment of the crowds. He cried out, ‘In the Name of Christ, stop!’ And his voice was lost in the tumult there in the great Colosseum…

And as the games began… the crowds saw this scrawny little figure making his way out to the gladiators and saying, over and over again, ‘In the Name of Christ, stop!’ And they thought it was part of the entertainment, and at first they were amused. But then, when they realized it wasn’t, they grew belligerent and angry…

And as he was pleading with the gladiators, ‘In the Name of Christ, stop!’ one of them plunged his sword into his body. And as he fell to the sand of the arena in death, his last words were, ‘In the Name of Christ, stop!’ And suddenly, a strange thing happened. The gladiators stood looking at this tiny form lying in the sand. A silence fell over the Colosseum. And then, someplace up in the upper tiers, an individual made his way to an exit and left, and the others began to follow. And in the dead silence, everyone left the Colosseum. That was the last battle to the death between gladiators in the Roman Colosseum. Never again did anyone kill or did men kill each other for the entertainment of the crowd…

One tiny voice that could hardly be heard above the tumult. ‘In the Name of Christ, stop!’ It is something we could be saying to each other throughout the world today.

How’s that for a New Year’s Resolution?

Bill Petro, your friendly neighborhood historian

billpetro.com

Podcast:

Subscribe to have future articles delivered to your email. If you enjoyed this article, please consider leaving a comment.