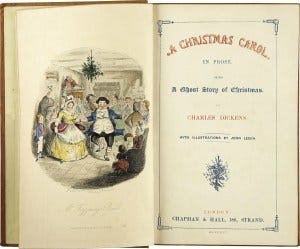

Charles Dickens’ novella A Christmas Carol was published in London on December 19, 1843. The first edition sold out by Christmas Eve.

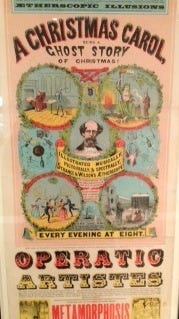

No other book or story by Dickens or anyone else (except the Bible) has been more enjoyed, referred to, criticized, or more frequently adapted to other media forms: theatre, opera, radio, film, TV, or comics.

One of my favorite versions was seeing Patrick Stewart perform his one-man version of the play at the Old Vic Theatre in London in the early ’90s.

Reinventing Christmas

None of Dickens’ other works is more widely recognized or celebrated in the English-speaking world. Some scholars have even claimed that, in publishing A Christmas Carol, Dickens single-handedly invented the modern form of the Christmas holiday in England and the United States. The movie The Man Who Invented Christmas argues that point.

Indeed, the great British thinker G. K. Chesterton noted long ago that with “A Christmas Carol,” Dickens transformed Christmas from a sacred festival into a family feast. In so doing, he brought the holiday inside the home. Thus, he made it accessible to ordinary people, who could now participate directly in the celebration rather than merely witnessing its performance in church. I wrote about the life of Charles Dickens a few years ago on the anniversary of his 200th birthday here.

A Traditional Christmas

Many of our American conceptions of what constitutes a “traditional” Christmas come from this time in Victorian history. Queen Victoria of England had married less than three years before the publication of this book.

Her German husband, Prince Albert, popularized some of his native customs in England (including the Christmas tree), beginning some of the traditions of Victorian Christmas. Dickens’ book popularized that style of celebrating Christmas in England and around the world at that time.

Ghost Stories in A Christmas Carol

The telling of melodramatic ghost stories, especially around Christmas, was widespread during the Victorian period. Dickens’ fascination with ghost stories, mesmerism, and spiritualism led him to include ghostly apparitions in his other works.

As a teenager, Dickens’s favorite was the penny weekly magazine The Terrific Register, which covered murder and ghosts. Reading it, he said he would “make myself unspeakably miserable and frighten my very wits out of my head.” This novella’s original title was

“A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost-Story of Christmas.”

Decline of Christmas

In the mid-seventeenth century, the Cromwellian Revolt abolished the monarchy and the celebration of Christmas in England. Though the monarchy was subsequently “restored,” the winter holiday traditions never quite recovered. However, the earlier religious prohibition was not the only cause of Christmas’ decline.

Even by the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution, especially in the north of England, changed the communities that still tenuously kept the customs of their ancestors.

When A Christmas Carol was written in 1843, the past’s lavish celebrations were a distant, quaint memory.

Some still remembered them, and even before the Carol, a few popular books attempted to record past celebrations, such as The Book of Christmas by T.H. Hervey (1837) and The Keeping of Christmas at Bracebridge Hall by Washington Irving (1820).

But social forces beyond simple nostalgia were at work, rekindling the need for winter celebrations.

Christmas Revival from A Christmas Carol

Dickens was one of the first to show his readers a new way of celebrating the old holiday in their modern lives. His Christmas celebrations of the Carol adapted the twelve-day manorial (Yule) feast to a one-day party any family could hold in their own urban home.

Instead of gathering together an entire village, Dickens showed his readers the celebration of Fred, Scrooge’s nephew, with his immediate family and close friends, and also the Cratchit’s “nuclear family”: perfectly happy alone, without the presence of friends or wider family. He showed the urban, industrial English that they could still celebrate Christmas, even though the old manorial twelve-day celebrations were out of their reach. Dickens’ version of the holiday evoked the childhood memories of people who had moved to the cities as adults.

Some have called the book a “sledgehammer” against the ills of industrialism and consumerism. Dickens’ own father had been sent to London’s Marshalsea debtors’ prison. Charles Dickens bitterly remembered having to leave school and work in a boot-blacking factory at 12 near Covent Garden. He’d seen children working long hours in the tin mines and attending poor schools.

He modeled Bob Cratchit’s lifestyle on his own experiences living in Camden Town, London. Dickens demonstrates that even in poverty, the winter holiday can inspire goodwill and generosity toward one’s neighbors. He shows that the spirit of Christmas was not lost in the race to industrialize but can live on in our modern world.

Initial Publication of A Christmas Carol

The publishing of his book was immensely popular — its initial printing of 6,000 copies sold out in three days, by Christmas Eve — and within six months, it sold out its seventh edition. By 1860, its thirteenth edition had been published. A Christmas Carol is generally associated with the Christian winter holiday season, for it does contain references to Christ from the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, as Bob Cratchit describes Tiny Tim talking about he…

“who made lame beggars walk and blind men see.”

At the end of the story, we see both lame Tiny Tim and blind Scrooge touched by the Spirit of Christmas. Nevertheless, the story’s themes are not exclusive to Christianity. It inspired a tradition for decades in Christmas books and celebrations that appealed to many non-Christians as well.

Public Performances of A Christmas Carol

It quickly was adapted to the stage in less than two months, and Dickens himself would read it during his speaking tours. It was his choice for his first public reading in 1852 and his farewell performance in 1870.

At Birmingham Town Hall, he initially did two performances to paying audiences but then requested the organizers to remove the seating and allow the working class in for free. They stood and listened. Following a silence at the end, they erupted into cheers and applause. He subsequently did a speaking tour of America.

He died in 1870, at age 58, about a month after his last public reading of A Christmas Carol.

Dickens’ preface to the book reads:

I have endeavoured in this Ghostly little book, to raise the Ghost of an Idea, which shall not put my readers out of humour with themselves, with each other, with the season, or with me. May it haunt their houses pleasantly, and no one wish to lay it.

– Their faithful Friend and Servant, C.D., December, 1843.

But the punch line to the book is the very last sentence, which rarely fails to bring a tear to the eye of this historian:

It was always said of Scrooge, that he knew how to keep Christmas well, if any man alive possessed the knowledge. May that be truly said of us, and all of us! And so, as Tiny Tim observed,

God Bless Us, Every One!

Bill Petro, your friendly neighborhood historian

billpetro.com

Subscribe to have future articles delivered to your email. If you enjoyed this article, please consider leaving a comment.