During the early Roman Empire two millennia ago, an emperor might be deified after he died if he was popular and good. (Think: the Divine Augustus.) Alternatively, if he was unpopular and wicked, he was “erased” from society’s memory.

The Latin term Damnatio Memoriae means the condemnation of the memory of a person by the Senate. The practice of the abolition of a person’s name is ancient.

Is this similar to the modern “cancel culture?”

Q: Why haven’t we heard more about this?

Because it was erased! Well, not completely, and sometimes not permanently. You know of someone who was erased, but you probably didn’t realize it, as I’ll explain.

Divine Augustus

Augustus, the first Emperor of Rome, portrayed the empire as a family under the emperor’s benevolent rule, and he passed legislation penalizing divorce, adultery, and familial disobedience. In contrast, he conferred political advantages upon fathers of three or more children. Bachelors who shirked “the duty of marriage” were penalized in their right to inherit, and they could not even secure good seats at the games! The census he ordered, mentioned in the Nativity story, may have been to evaluate the result of his reforms.

Maison Carree, Temple of Augustus, Nimes, France

Upon his death, in 14 A.D., he was deified with the divinely sanctioned authority of the Roman State. The Senate elevated him in the act of apotheosis (“to deify a human”). Temples throughout the Empire were built for him; an Imperial cult was developed around him. He even got a month named after him.

About 25 Roman emperors were deified or consecrated after their death.

Emperor Nero

Nero, the fifth Emperor of Rome, was one of the most infamous Emperors of the Imperial period.

Though the first five years of his reign were viewed positively, he was later associated with extravagant living, a debauched lifestyle, and tyranny. He was heir to his great-uncle Claudius (made famous by the TV-series I Claudius) and succeeded him at 17. His mother Agrippina (whom he later killed) and his tutor Seneca guided the early years of his reign. He also killed his first wife and rival step-brother Britannicus. He fancied himself a great actor, musician, and charioteer. He showered his subjects with theatres and games.

Although Nero’s “bread and circuses” were popular with the lower classes, the larger population lost respect for his authority and office, realizing that he had emptied the treasury.

He instigated the Great Fire of Rome in 64 A.D. to clear out room in the city ahead of his planned palatial domicile Domus Aurea, or Golden House on the Palatine Hill, near the Roman Forum. But this backfired on him, and instead, the fire destroyed two-thirds of the city.

Needing a scapegoat for the fire, he blamed the fire on the Christian community in the city. This led to the first Imperial persecution of Christians. According to the Annuls written by the Roman historian and senator Tacitus, Nero saw to it that

“Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired”

…for his dinner parties.

Finally, in 68 A.D., one of his territories revolted against him, and the army chose his rival General Galba as the next emperor. After fleeing Rome and hearing that he’d been tried in absentia and condemned as a “public enemy,” he committed suicide at the age of 30 — likely rather than be assassinated — the first Roman Emperor to ever do so. With his death, the Julio-Claudian dynasty, founded by Augustus, came to an end. A year of brutal civil war followed. Even his palace was later replaced with baths by Emperor Trajan.

Q: What’s the part of Damnatio Memoriae that you know but didn’t realize?

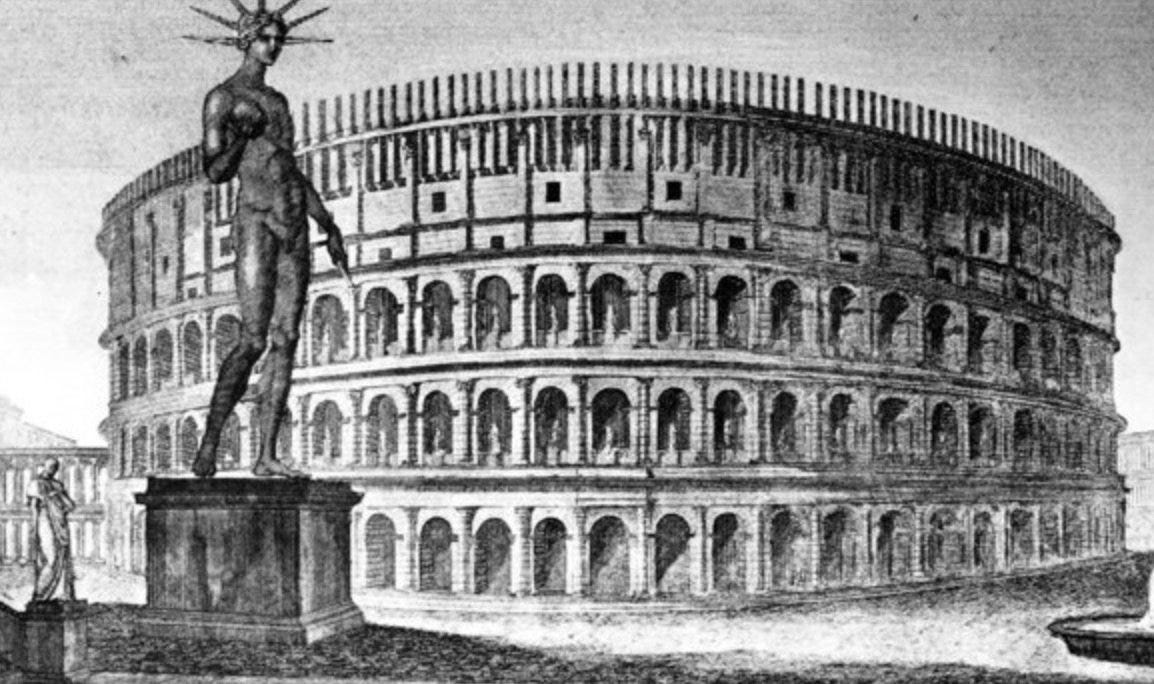

If I asked you what the large amphitheatre near today’s Roman Forum is called… you’d say the Colosseum. But that wasn’t its original name. Vespasian, the emperor after Nero originally built it. It was named upon its completion in 89 A.D. the Flavian Amphitheatre in honor of his family name and subsequent dynasty: Flavius.

Colossus of Nero

Why is it now called the Colosseum?

Nero built a 100-foot high bronze statue, a Colossus with his face on it. This Colossus Neronis, patterned after the Colossus of Rhodes, stood as high as the Statue of Liberty. It was a self-testament to his glory.

After his death and the Senatorial condemnation, the statue was defaced and replaced with the sun god’s face, Sol. Twenty-four elephants eventually moved the statue to a spot outside the Flavian Amphitheatre, which became known, by its proximity to the Colossus, as the Colosseum.

He was erased in other ways.

Defaced and clipped Nero coin

The Senate would destroy the images of such condemned figures. Their heads would be removed from statues. Their names were erased from inscriptions by abolitio nominis, “the abolition of one’s name.” If the doomed person were an emperor or other government official, even his laws could be rescinded. Coins bearing the image of an emperor who had his memory damned would be recalled, canceled, or have the inscription or face scratched.

Between the reigns of Augustus and Claudius…

Name scratched off Sejanus coins

The Roman Prefect and imperial bodyguard Sejanus, who I’ve mentioned in the history of Pontius Pilate, failed in his coup against Emperor Tiberius. The Senate denounced him, and he was promptly executed by being publicly strangled and thrown down the Germonian Steps in Rome. There, his body was beaten and thrown into the Tiber River. His name was scratched off coins that were minted during his Consulship in 31 A.D.

Through the end of the 4th century, as many as 35 emperors had their memories condemned. Some of the names you may be familiar with are:

Caligula (Gaius, known for his blatant debauchery), was subjected to this condemnation, but his uncle and successor Claudius shot down the Senate’s attempt.

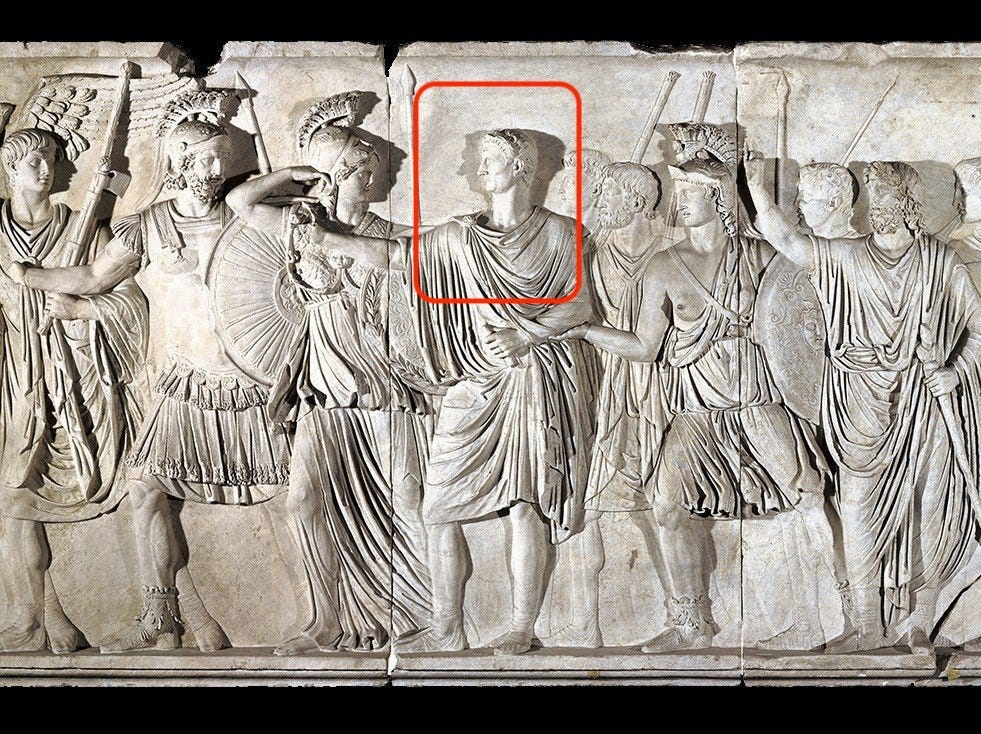

Domitian (first empire-wide persecution of Christians, according to the church historian Eusebius.) There is a relief carving of Domitian departing from Rome on a military campaign, ushered out of the city by Victoria, Mars, and Minerva and personifications of the Senate and the Roman people. Yet the head atop the stately tunic-clad body of the emperor is not that of Domitian. Instead, it is Nerva who succeeded Domitian after the latter’s assassination and subsequent damnatio memoriae.

Nerva replaces Domitian in Cancelleria Reliefs at Vatican Museum

Commodus (made infamous by the movie Gladiator) had his body dragged through the dust, and his statues overturned.

Decius (second empire-wide persecution of Christians).

Diocletian (last, largest, and bloodiest empire-wide persecution of Christians).

Under Emperor Constantine, Christianity became the preferred religion. When Christianity became the official state religion under Emperor Theodosius I, damnatio memoriae was no longer practiced in Rome.

Q: What are other notable examples throughout the history of Damnatio Memoriae?

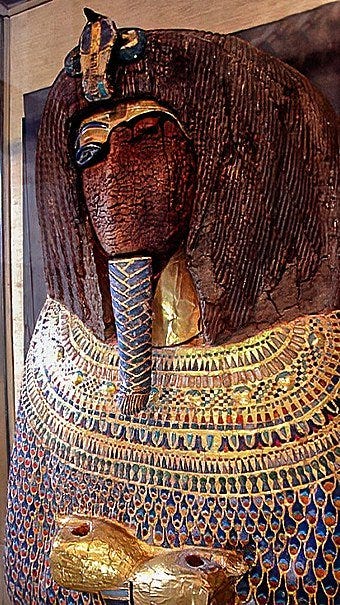

The obliterated face of Akhenaten

There were ancient versions of this before the Romans: the Egyptians “erased” King Tutankhamun’s father, Akhenaten. His name, along with those of his relatives, was erased from records and no longer appeared on the list of Pharaohs. His face was obliterated from his tomb coffin.

The Greeks did something similar. At the Battle of Thermopylae of 480 B.C., a traitor exposed the Spartans’ location and a backdoor trail to their Persian enemies. Subsequently, they banned the name of this traitor, Ephialtes of Thrachis, from being recorded in Spartan history.

Spartans in the movie 300

The Greek historian Herodotus only learned of the name when he visited Thessaly because Spartans would not utter the name. Thereafter the name came to mean “nightmare” in Classical Greek, a synonym to “Benedict Arnold.”

In more recent times…

During the time of the Soviet Union, Josef Stalin would write people out of the Bolshevik narrative when they lost favor. Pictured below is Nikolai Yezkov, head of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, who fell out of favor and was tortured. Records and photos of him disappeared.

Stalin and Nikolai Yezkov

Q: Is Damnatio Memoriae the same as today’s “cancel culture?”

There are some apparent similarities but some notable differences. It was usually reserved as a punishment for important government officials, Emperors, Senators, and Generals and typically done posthumously.

Importantly, this condemnation was carried out by the government, in this case, the Roman Senate. It was not done by the populace or popular opinion.

However, sometimes the populace did not agree with the Senate and favored the memory of those so damned.

Damnatio Memoriae was not completely successful in wiping out the memory of an individual. Among the emperors who suffered damnatio memoriae are some of the best-known figures from Roman history. These men’s notoriety comes to us from texts written during their lifetimes and later and from images that survived the immediate violence of the damnatio memoriae and then centuries of neglect.

Damnatio Memoriae is an example of government “censorship” in the original meaning of the word. It is the political working, by those in government, “to conceal, distort, delete or falsify information that its citizens receive by suppressing or crowding out political news that the public might receive through news outlets.” In Roman times this consisted of statues, public works, inscriptions, and official acts.

Q: What is different today about Damnatio Memoriae?

“Cancel culture” is not like what we see above for several reasons… but there are some interesting adjustments for changes across history.

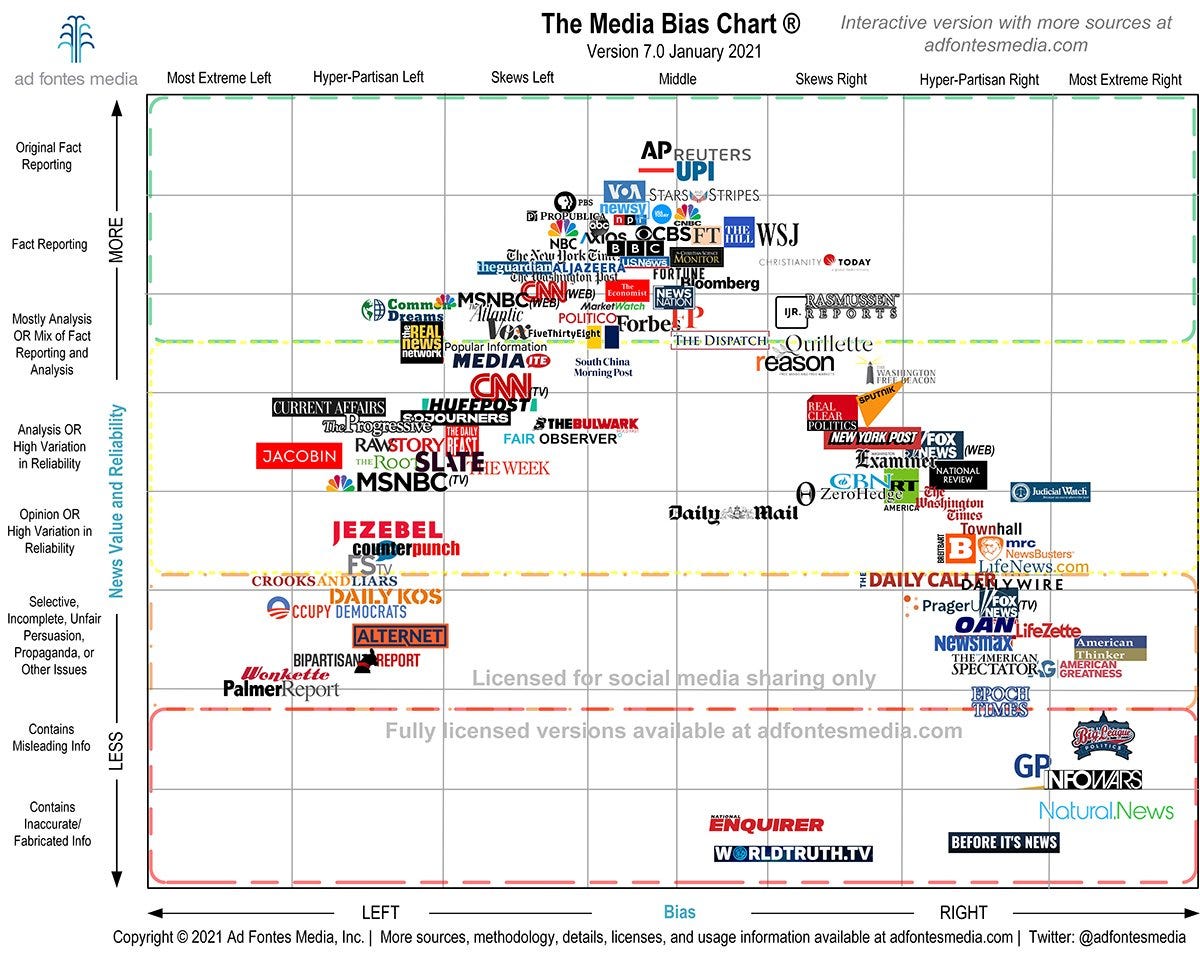

While censorship by various government administrations still occurs, it is beyond the scope of this article. Instead, “cancel culture” is exercised in the media, in its various forms, especially on the Internet. It works on a popular rather than governmental level to boycott or ostracize a voice or a viewpoint.

The origin of the term “cancel culture” is recent, coming out of 21st-century “safetyism” on college campuses and anecdotally out of popular movies and hip-hop music. It is practiced primarily on social media with its reach and speed. It has progressed to an insistence of tolerance of all opinions as long as they match one’s own.

The targets are usually public figures: celebrities, companies, brands, politicians, and thought leaders.

Ironically, it has become a kind of modern-day neo-Victorianism, used as a tool for “virtue signaling” or “social justice.” Victorians were at least socially moral, but modern practitioners of the cancel culture make no such claim. Cancel culture is the merchandising of shame parading as accountability holding. The winds of themes and memes change with the latest fads, regardless of the accusers’ hypocrisy. This can and has lead to online mobs and hivemind group thinking. Think: tribalism gone bad.

The most recent examples of its use include having one’s account suspended from social networks, being “de-platformed” in the public square of online discourse. But these are not government platforms; public companies own these social networks.

But what happens when the media, on either side of the partisan divide that I mentioned as an example in my previous article on The Press, takes the side of one political party or the other? There have been accusations of that recently on both sides of the political aisle. When this occurs, the Fourth Estate becomes a proxy for campaigning on behalf of these political leaders or suppressing opposing political views by preventing them from reaching the public. When this happens, then it becomes like Damnatio Memoriae, but now with living government leaders.

If you’re keeping score, there’s a browser plugin from ground.news that shows a banner at the top of news stories, indicating which way the publication leans: left, right or center.

Perhaps the most fascinating examples are the revisionist history that dismantles the Founding Fathers for their perceived shortcomings, according to the latest fashion in “unforgivable sin.” Is removing their names from schools or other establishments and taking down their statues any more than examples of historical vandalism?

Does our generation believe that we have achieved the moral perfection that ensures the insight, wisdom, and authority to judge rightly previous generations? Do we presume that the future will look kindly upon our own moral failings? As Thomas Jefferson said, I’m sure self-consciously,

“Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep for ever.”

Modern erasures

A recent funny-if-it-weren’t-so-sad example is the San Francisco Board of Education voting to remove the names of 44 public schools — with names like Washington and Lincoln — without the benefit of having anyone on the board who knew how to do historical research beyond Google searches. It’s like voting down the “next celebrity” contestants on American Idol.

And ripped from this week’s headlines: Students demand the removal of George Washington’s statue from the University of Washington, in the state of Washington.

Why would we think we get to vote on history like it’s clicking the down-arrow on an article we dislike? History judges us. And if we’re wise, we learn from history.

The antidote: investigating and understanding the larger historical perspective and the context of our complex heritage.

“Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past”. — the Party’s slogan, “1984” George Orwell

Bill Petro, your friendly neighborhood historian

billpetro.com

If you enjoyed this article, please consider leaving a comment. Subscribe to have future articles delivered to your email.