We know this polymath as a writer, publisher, printer, merchant, scientist, moral philosopher, international diplomat, and inventor.

He invented the glass harmonica in music, but he also invented the Franklin stove and started the first lending library and fire brigade in Philadelphia.

He did experiments with electricity and developed the lightning rod. He was considered:

America’s best scientist, inventor, diplomat, writer, and business strategist, and he was also one of its most practical, though not most profound, political thinkers. – Walter Isaacson. Benjamin Franklin: An American Life

Ben Franklin in America

Born in Boston on January 17, 1706 *, he was among the earliest and oldest of the American Founding Fathers. He served as a lobbyist to England, was the first Ambassador to France, and has been called “The First American.”

He was one of the five drafters of the American Declaration of Independence, along with John Adams and primary drafter Thomas Jefferson. Franklin was 70. At 81, he served as the oldest delegate at the Constitutional Convention.

Ben Franklin in France

Franklin’s Marten Fur Cap

During the Revolutionary War, he served as Minister to France. With his sagacity and salon celebrity, he convinced the French King Louis XVI to support the American cause financially and militarily. He dazzled the salon crowd with his notoriety and flirtation, much to John Adam‘s chagrin.

When a person appeared before the French king in Versailles, it was always without a hat. Franklin showed up in a marten fur cap. They loved him. Franklin captivated Paris society.

Cafe Precope, Paris

He frequented the first, and still to this day, the oldest coffeehouse in Paris, the Café Procope, as did other luminaries like Thomas Jefferson, John Paul Jones, Voltaire, and a young Napoleon Bonaparte.

While it is hard to imagine in a world of royalty and celebrities, Franklin was America’s most famous private citizen and the most celebrated American in Europe.

Though he never went past the second grade in school, he was often called “Doctor Franklin” publicly. He was awarded an honorary Doctorate by the University of St. Andrews and Oxford University and honorary Masters Degrees at both Harvard and Yale.

Ben Franklin in Philadelphia

Following the Constitutional Convention of 1787, as Benjamin Franklin exited the Philadelphia State House, he was reportedly asked by the outspoken Mrs. Elizabeth Willing Powel of Philadelphia, the leading American saloniste acquainted with John Adams and a close personal friend of George Washington,

“Well, doctor, what have we got, a republic or a monarchy?“

Franklin’s famous reply was,

“A republic, madam, if you can keep it.“

Ben Franklin’s Moral Philosophy

As a moral philosopher, he was a personal mystery. Though he believed that the new Republic could survive only if its citizens were virtuous, he wrote pithy and wise sayings in “Poor Richards’ Almanac” — he did not live by all of them himself. He is usually considered a deist, at least in his early life. Nevertheless, he proposed clergy-led prayer each morning during the Constitutional Convention in June 1787.

He said

“God governs the affairs of men”

yet he also said,

“I have some doubts as to [Jesus’] divinity.”

He was a huge fan and supporter of the international evangelist George Whitfield and would go on to publish all his sermons. But he did not subscribe to Whitfield’s theology.

Was Ben Franklin a Deist, or…

Puritan Ezra Stiles, president of Yale, knew of Franklin’s deist leanings but wanted, if possible, to pin down the nimble-footed freethinker to some basics. In friendship, Stiles asked for some kind of creedal confession, however limited. Franklin, who said that this was the first time he had ever been asked, on March 9, 1790, readily obliged:

“Here is my creed. I believe in one God, Creator of the universe: that he governs the world by his providence. That he ought to be worshiped. That the most acceptable service we can render to him is doing good to his other children. That the soul of man is immortal and will be treated with justice in another life respect[ing] its conduct in this. These I take to be the fundamental principles of all sound religion, and I regard them as you do, in whatever sect I meet with them.“

Also, Stiles wanted to know specifically what Franklin thought of Jesus: Was Franklin really a Christian or not? Franklin responded that Jesus had taught the best system of morals and religion that “the world ever saw.” But on the troublesome question of the divinity of Jesus, he had, along with other deists, “some doubts.”

It was an issue, he said, that he had never carefully studied and, writing only five weeks before his death, he thought it

“needless to busy myself with it now, when I expect soon an opport[unity] of know[ing]the truth with less trouble.”

It would be difficult to burn a heretic like that.

Ben Franklin’s Epitaph

For his own epitaph, Franklin wrote at the age of 22:

“The body of Benjamin Franklin, printer, like the cover of an old book, its contents torn out, stripped of its lettering, and gilding, lies here, food for worms. But the work shall not be lost; for it will, as he believed, appear once more in a new and more elegant edition, revised and corrected by the Author.“

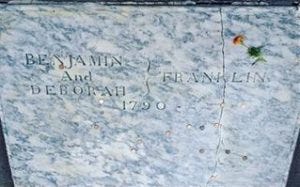

After he died, though, 62 years later, at 84, his will stipulated that on his gravestone appear only “BENJAMIN And DEBORAH FRANKLIN 1790.” His funeral in Philadelphia attracted the largest crowd of mourners ever known, an estimated 20,000 mourners.

Gravestone of Ben and Deborah Franklin

*Or was he born on January 6?

Significant parts of the Western world changed from the Julian Calendar to the Gregorian Calendar in the mid-1700s. However, when Pope Gregory XIII of the Roman Catholic Church decreed the calendar fix, not everyone embraced the change. In fact, Great Britain was not a fan of the Roman Catholic Church then, and many in England protested the calendar change. Those born in that gap lost 11 days of their lives: following Wednesday, September 2, 1752, came Thursday, September 14.

September 3 instantly became September 14, and, as a result – as explained at Project Britain – nothing happened between September 3 and 14, 1752. In other words, The British Calendar Act of 1751 proclaimed that in Britain (and her American Colonies), Thursday, September 3, 1752, should become Thursday, September 14, 1752. Franklin embraced the change, though others in England and America remained slightly upset.

Bill Petro, your friendly neighborhood historian

billpetro.com

Subscribe to have future articles delivered to your email. If you enjoyed this article, please consider leaving a comment.