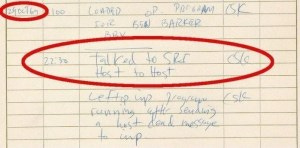

On October 29, 1969, at 10:30 PM, a computer grad student at U.C.L.A. named Charley Kline sent a message to S.R.I. (Stanford Research Institute.) It was the first connection between computer networks. The Internet began!

We set up a telephone connection between us and the guys at SRI…

We typed the L and we asked on the phone,“Do you see the L?”

“Yes, we see the L,” came the response.We typed the O, and we asked,

“Do you see the O?”

”Yes, we see the O.”Then we typed the G, and the system crashed…

Yet a revolution had begun…

Q: What is the Internet?

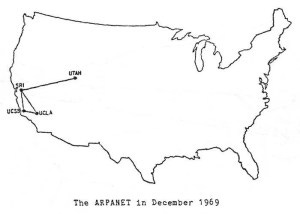

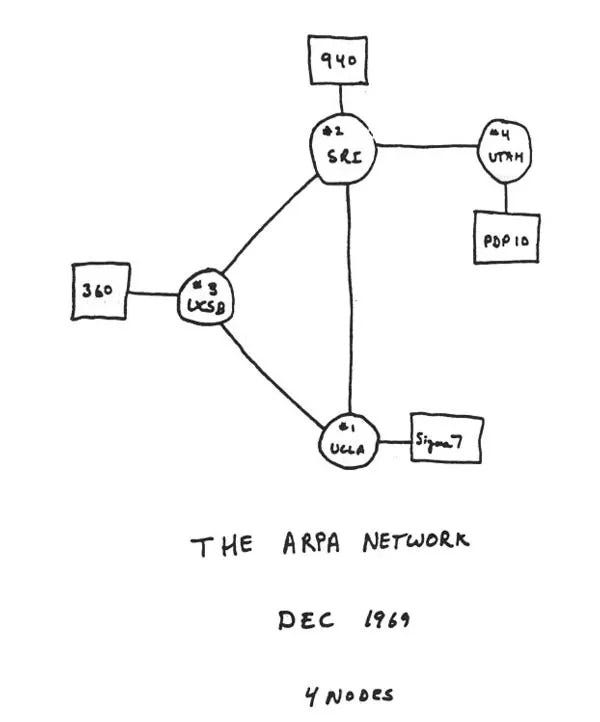

It’s the “network of interconnected networks.” By that definition, August 29 was the beginning. It was funded by ARPA (Advanced Research Projects Agency, founded by the U.S. Department of Defense) and became known as ARPANET. Four universities were initially connected: U.C.L.A., Stanford, UC Santa Barbara, and the University of Utah.

Background

Computers in the ’60s were used primarily for scientific research across universities and labs. The U.S. government wanted a network that would permit computers to communicate automatically even if some telephone lines connecting them were interrupted.

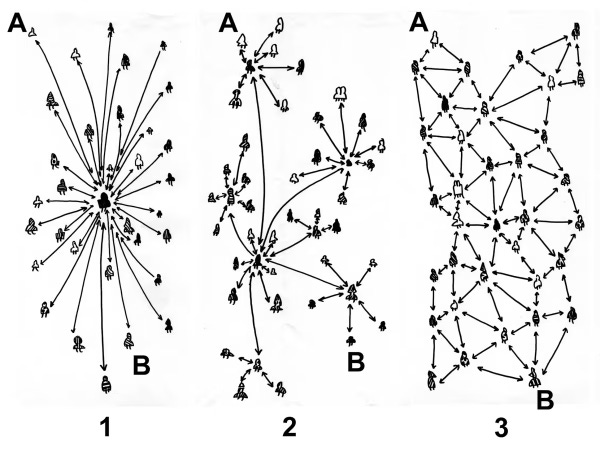

To get a message from A to B, which type of network is most likely to keep working if some of the lines are cut? P2P Topology by Txelu Balboa: Image: Wikimedia Commons

Network 1, with a single central computer connected to the others as spokes, wouldn’t survive a broken connection. Network 2, with several of these hub-and-spoke networks, would not survive either. But Network 3, where every computer is connected to many others forms a mesh.

Q: Is that all there is to it?

There is much more to the history, both before and after. Vint Cerf, “the father of the Internet,” now VP at Google, developed TCP/IP (Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol) as the universal language that enabled computers to talk to each other over the “Internet” via Ethernet cables. He submitted the design to the IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) in 1974, and in 1981 a complete specification of TCP/IP protocol was created.

Vint explained it as “an engineering problem intended to be a resource for sharing time on different brands of computers”—and there were many brands back then.

December 1969—the U.S. Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) connected four computer network nodes at the University of California, Los Angeles, (U.C.L.A.), the Stanford Research Institute (S.R.I.) in Menlo Park, Calif., U.C. Santa Barbara (U.C.S.B.), and the University of Utah. The “Sigma 7” note next to the circle depicting the U.C.L.A. node refers to the Sigma 7 computer at U.C.L.A.’s Network Measurement Center that Vint Cerf connected to ARPANET.

Q: Is the Internet synonymous with the World Wide Web?

No, though confusingly, many people use the terms interchangeably. But they’re not identical.

Q: How is the World Wide Web different from the Internet?

At the risk of oversimplifying, I like to say that the World Wide Web is a “personality” of the Internet. Stated differently, people used to work on the Internet with a command-line interface, typing commands, usually into a UNIX console, using a variety of protocols. This was classical Geek. You had to know these commands by heart.

Over the following years, esoteric programs like wais, search engines like Archie, and protocols like Gopher allowed the I.T. high priesthood to navigate this nascent platform. I first got on the Internet in 1985 when the startup I was working for got access to Sun Microsystems, part of the main backbone of the Internet at that time.

Then two things happened beginning at the end of the ’80s:

Like moving from Morse code to a graphical presentation of information…

1) On March 12, 1989, Tim Berners-Lee of Oxford, a physicist and researcher at the High Energy Physics lab at CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research) in Geneva, developed a hyper-text methodology of connecting a page of information to another with “links.”

He called this protocol HyperText Transfer Protocol or HTTP. You see it at the beginning of a web link. His team also developed URLs (Universal Resource Locators) and the HTML (HyperText Markup Language) to create websites.

Sir Tim Berners-Lee became the director of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). He was awarded the renowned Turing Prize for inventing the World Wide Web, algorithms, and protocols that allowed it to scale. The first-ever website can be found here.

Q: When did the W.W.W. start?

2) In 1993, Marc Andreessen worked at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) at the University of Illinois, where he met Tim Berners-Lee. Andreessen developed this user-friendly computer program called a “web browser,” which he called Mosaic.

It allowed people to see a graphical representation of a “page” on their computer. The pages were displayed in text and pictures. Objects or words could be clicked on with a mouse, and you could jump to another page elsewhere on the Internet.

The following year, while working at Sun Microsystems, I got my hands on the browser and created my first internal Product Marketing website.

Back then, you could read the Web’s “What’s New” page, which discussed all the new websites that had appeared overnight. You can’t do that anymore.

Andreessen came to Silicon Valley, just down the road from where I worked at Sun Microsystems and started Netscape, the commercialization of the Mosaic browser. (It is also the basis for Internet Explorer, but that’s a long story.)

He licensed a technology called Java from Sun (I was a Java evangelist for Sun) for inclusion in his browser. His company had developed a scripting language called LiveScript, which Sun convinced him to rename to JavaScript.

Q: What happened next?

In 1989, commercially available dial-up Internet Service Providers (I.S.P.s) became available with a modem — MOdulation/DEModulation – to convert a computer signal to a phone signal and back again — allowing non-technical users to access the Internet. Popular options included CompuServe and America Online (AOL). Email had been developed a decade and a half earlier, but now average users could log in to AOL and hear “You’ve Got Mail.”

We called this phenomenon, in retrospect, Web 1.0. Instead of “the Net,” we now say “the Web.” Although “www” was available to the public, few knew about it or had access to it. Those of us at high-tech companies like Sun, or those at universities, weapons labs like the Department of Energy’s Laurence Livermore National Labs, Sandia, or Los Alamos, or major defense contract companies did know about it. They used it regularly through the ’70s and ’80s.

Most people didn’t see a standard, non-proprietary computer browser until 1995 or 1996. I created billpetro.com in 1995, as more people had access to the “Web” then. I could now host my history articles on my website, which I had previously posted to the newsgroups on USENET.

In 1995, Amazon.com, Craigslist, and eBay came online. Starting in 1998, the Google search engine began to obsolete all others, including Alta Vista and Yahoo’s search.

In 1996-97, I traveled the world talking about the Internet, Intranet, and Java.

In 1998-99, the dot-com world expanded. In 2000 there was a dotbomb as many overvalued “web companies” crashed.

Q: What about Web 2.0?

Popularized in 2004, what we called Web 2.0, or the second generation of the Internet, was an attempt to move beyond static web pages, or “brochureware,” to create interactive content.

The term was overhyped and overused at the time, but it did give rise to the explosive and infectious use of social media and social networks. This would include early examples like MySpace and GeoCities and later examples like Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn. Weblogs or Blogs could be created by using Blogger, LiveJournal, and WordPress.

Q: Is the Internet revolution over?

Not by a long shot. We are not even at the beginning of the end, more like the end of the beginning. With the advent of smartphones in the early 2000s and the popularity brought by the introduction of Apple’s iPhone in 2007, the use of data networks and WiFi technology took the Internet mobile. More people access information online via “apps” (applications) on mobile devices than any other computer.

And not just mobile phones, but smartwatches and exercise devices communicate data wirelessly to and from the Internet. We now see these interconnected devices as the Internet of Things.

Q. How many devices are there on the Internet of Things (IoT)?

There are billions of IoT devices, but the number is growing. There are 10B today; by 2025, 152K devices will be connecting to the Internet per minute, but over 25B are expected by 2030. Network-connected devices include sensors, cameras, and telemetry that “stream” huge amounts of “unstructured” data from the “edge” of the Internet to vast data lakes of information to be processed by Big Data analytics engines which help companies and individuals gain insights to make critical decisions.

WiFi and now Bluetooth-connected devices include smartphones, headphones, hearing aids, pacemakers, house security cameras and alarms, thermostats, robotic vacuum cleaners, house lights, and coffee mugs.

Ember coffee mug

I’m not kidding; each morning, I pour my cappuccino into a mug that has an embedded heating coil and battery. Via Bluetooth, it connects to an app on my iPhone that will keep the coffee at a set temperature, at least until the battery runs out.

The future of the Internet is calling… you can answer it on your Apple Watch.

Bill Petro, your friendly neighborhood historian

billpetro.com